Details

Images: © Iwan Baan

At Litelab, we embrace unique projects and the design challenges that they present. That’s when we get to stretch our creative muscles. When we were approached to manufacture a one-of-a-kind chandelier designed by Konstantin Grcic for the Parrish Art Museum, we jumped at the opportunity. Not only did we get to develop a distinctive set of chandeliers, but it was also a chance to work with Swiss architecture firm, Herzog & de Meuron. Balancing the ambitious design of these signature fixtures with budgetary constraints posed a special challenge that took significant knowledge of rigging, advanced manufacturing techniques, and a little bit of whimsy to solve.

Situated in Long Island Sound and surrounded by farmland, this site is extremely secluded. Instead of using this landscape to create a bold 3-dimensional object that would stand out from its surroundings, Herzog & de Meuron designed an incredibly restrained building inspired by regional agricultural architecture. The museum (which looks similar to an extruded barn) blends into its surroundings, paying homage to the site and the region in which it is located.

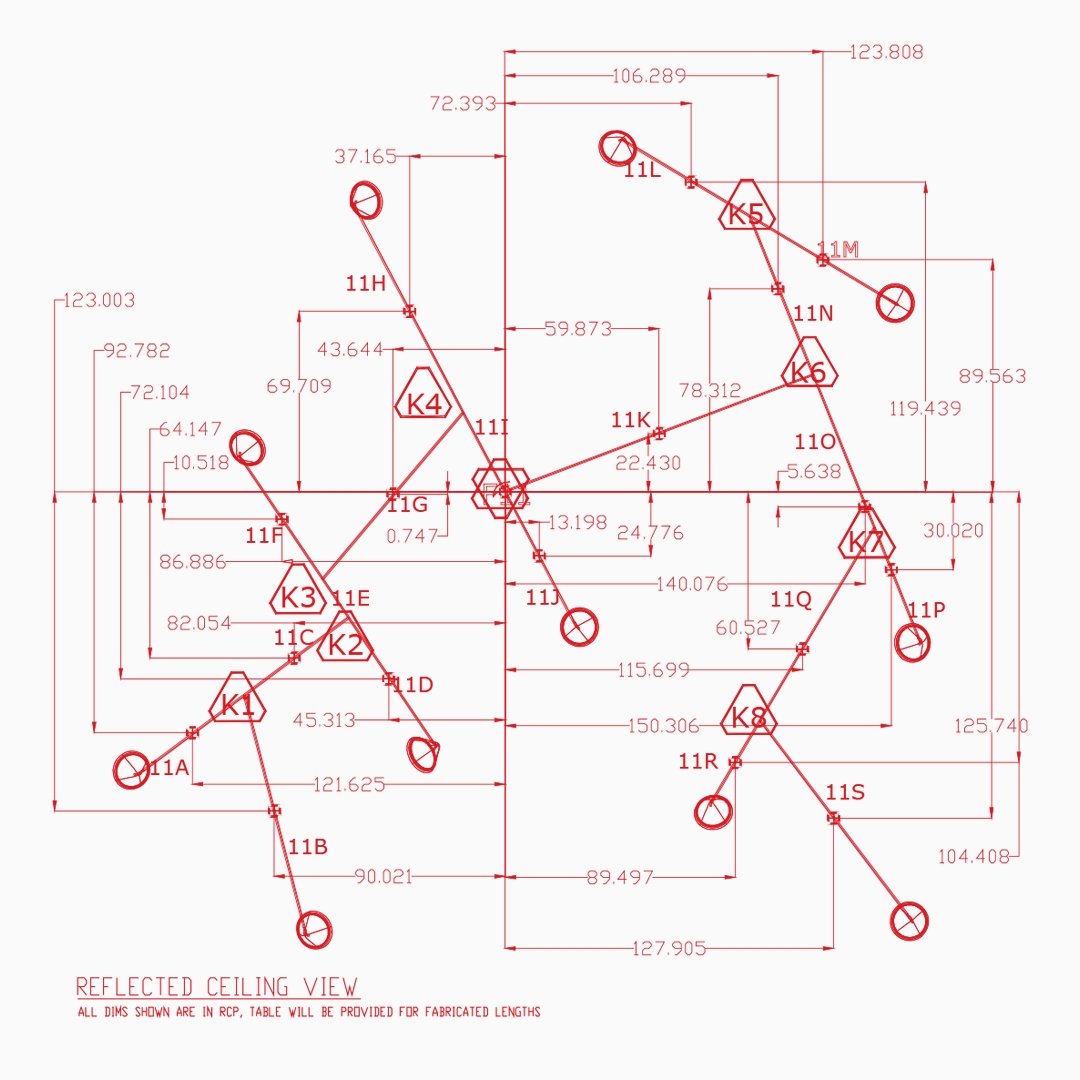

Once inside, the visitor is confronted by Grcic’s chandeliers, a truly remarkable work of art and industrial design. Branching from supporting nodes, cantilevered arms undulate across the ceiling, creating a floating spider web of lights and knuckles, resulting in a scene that is at once organic and mechanical.

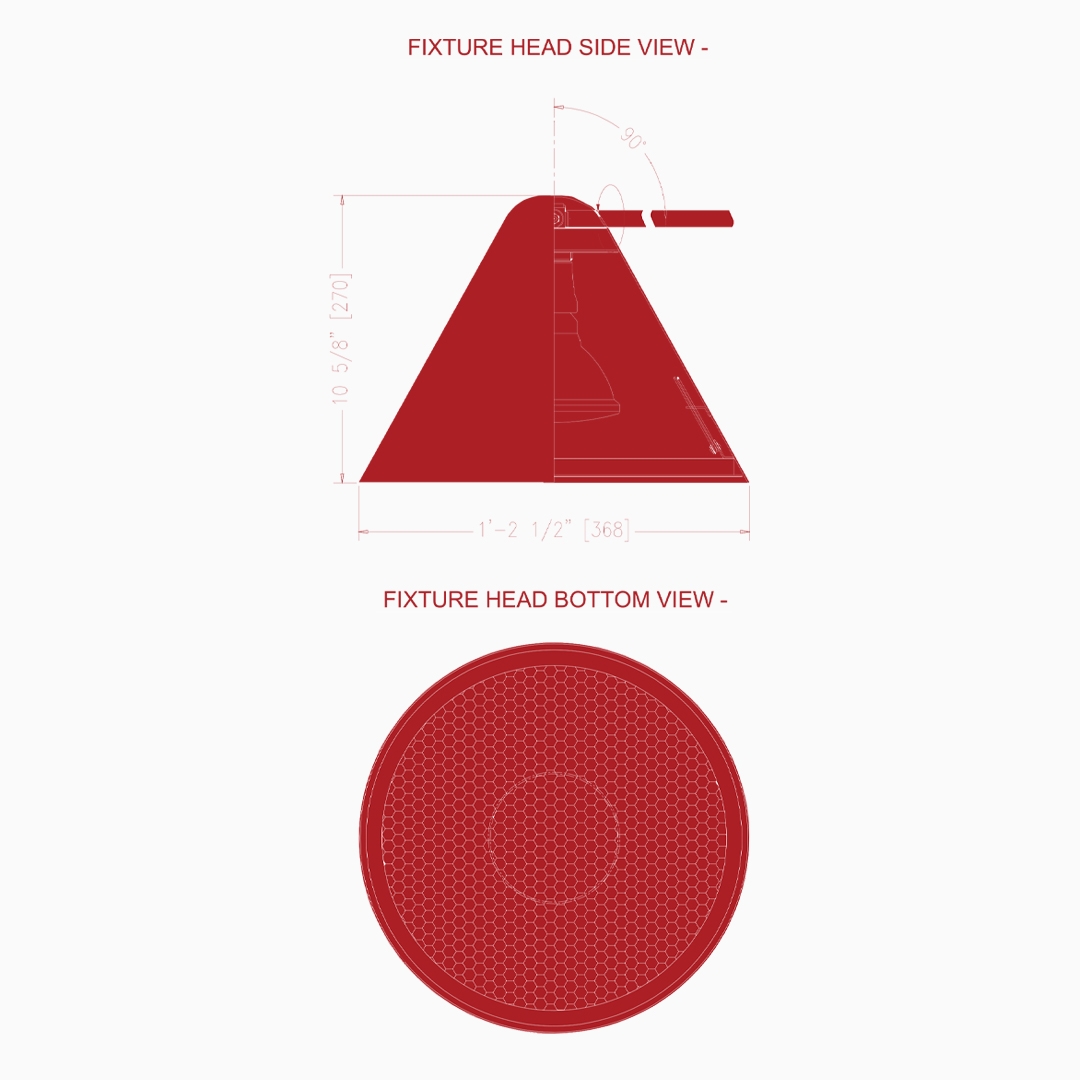

The design posed three specific challenges - first was rigging the massive Caulder-like chandeliers with minimum hang-points to maintain the airy, branch-like aesthetic; second was spinning the large blossom-like lamps in which each branch culminates; third was precisely machining over one hundred unique knuckles while staying within budgetary constraints.

Caption: A mockup of the chandelier layout from the ceiling

Luckily, Litelab has a strong background in theatrical lighting, which we used to develop the intricate rigging that makes the design appear so light. Our in-house designers developed means of reducing member weight, while balancing and counterbalancing the branches as they spread through space using minimum hanging points. The structure works in poise and counterpoise, as the thin arms and reduced supports contribute to a sense of effortlessness and weightlessness, concluding in large, spun, conical-shaped lamp-shades, reminiscent of calla lilies or cherry blossoms.

Manufacturing the shades and the knuckles posed their own challenges, each with a unique response. For the shades, Litelab is fortunate to continue a craft tradition of hand-spinning in our factory in Buffalo, NY. While this craft has been largely replaced by digital spinning, manufacturing low quantities of unique shapes by hand can provide cost savings, and allows Litelab to respond more agilely than firms with totally digital infrastructures. As a result, we were able to fabricate the iconic calla lily shades of the chandeliers in house at lower cost.

In a manner not unlike the way the chandelier uses force and counterforce, the solution for the knuckles represents the opposite extreme from the hand-crafted method for shade production. To support all of the branches, the chandeliers require over a hundred entirely unique knuckles. Machining these by hand would have been prohibitively expensive, so Litelab sought alternative means for fabrication.

In 2013, 3D printing was just beginning to gain momentum. We wondered if 3D printing could be a cost-effective means of fabricating the knuckles — and found several firms in the US who were experimenting with 3D printed metal. After a period of working with several manufacturers to finalize the geometry and meet design constraints, while also minimizing secondary or tertiary machine operations, we settled on a partner and had each joint printed to specification.

The challenges behind the Parrish Art Museum chandeliers present several interesting questions in terms of means and methods of fabrication — how do we incorporate emerging and contemporary technologies to push design further than was previously possible? How do you determine which technological solution is best suited to a particular problem? Now that 3D printing with alternative materials is more common, many firms use it, and other advanced digital techniques to incorporate unique, scalable, one-off designs into architectural and interior design. Conversely, a new generation of craftspeople are synthesizing traditional fabrication techniques with advanced digital fabrication to generate items that include evidence of hand as a trace of artistry. Litelab’s contribution to the Parrish Art Museum represents both approaches as a reflection of the total design requirements of the project.