Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Architects: Herzog & de Meuron

Lighting Design: Flux Studio Ltd

Calder Gardens – Space, Time, Form & the Poetics of Joy

A mobile in motion leaves an invisible wake behind it, or rather, each element leaves an individual wake behind its individual self. Sometimes these wakes are contracted within each other, and sometimes they are deployed. In this latter position the mobile occupies more space, and it is the diameter of this maximum trajectory that should be considered in measuring a mobile.

Alexander Calder – Á Propos of Measuring a Mobile

Lurking behind Calder’s pragmatic advice is a subtle, poetic conception of the evolution of form in space and time. Earlier in this short essay, Calder describes the lightness of “deployed nuclei” in creating “an atmospheric condition, or even a void,” as opposed to the solidity of even perforated or serrated solids. Planes, surfaces and lines dissolve into a choreography of interacting cells, undulating, collapsing and dispersing, vibrating with borrowed life.

While many of the shapes used by Calder have an organic sensibility (á la Miro), the true animal nature of his work is its interaction with the environment, what James Sweeney calls “the organization of contrasting movements and changing relations of form in space” in the MoMA catalog dedicated to Calder’s first solo show. As a result, exhibiting Calder, as his essay suggests, comes with its own unique challenges. This is not limited to scale, presentation and lighting, but extends to the various types of interactions implied by the works.

At the most abstract level, there is the dialogue between form, space and time. This is expressed as much in terms of movement as it is in terms of formal and spatial transformations. As the French Art Historian Henri Focillon argues in The Life of Forms, form inflects space as much as space affects form.

A work of art is situated in space. But it will not do to say it simply exists in space: a work of art treats space according to its own needs, defines space and even creates such space as may be necessary to it. The space of life is a known quantity to which life readily submits; the space of art is a plastic and changing material.

A space that delimits would be anathema to the formal and temporal demands of Calder’s work, which requires spaces that breathe, expand and contract, transform in relation to the metamorphosis induced through interaction.

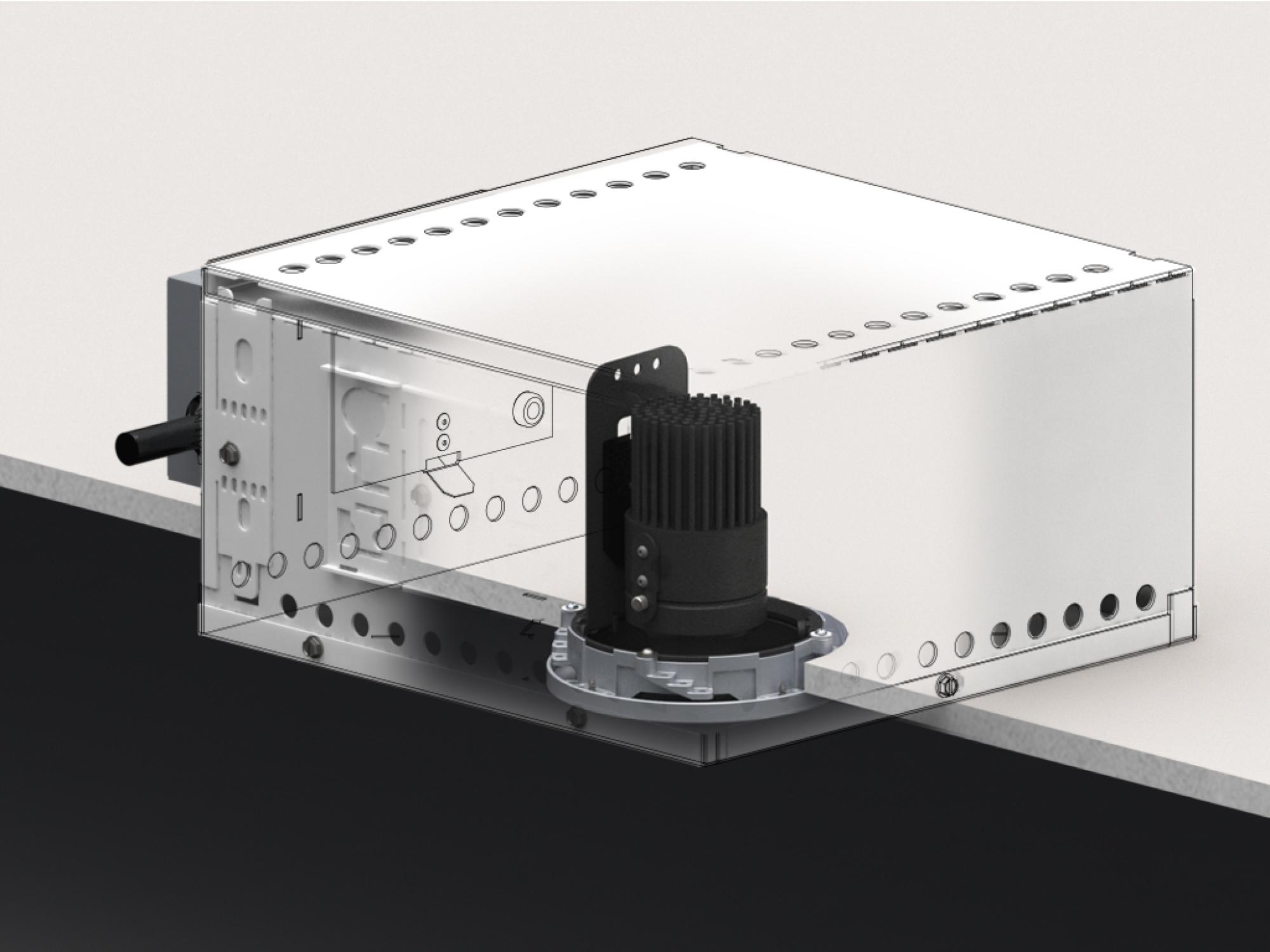

Calder Gardens, designed by Herzog & de Meuron with lighting design by Flux Studio provides an almost ecological approach to exhibiting Calder’s work. Located on a vestigial plot of land along Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Calder Gardens is bounded to the North by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and to the East by the Barnes Foundation and the Rodin Museum. Eschewing monumentality, the museum shows a reserved, vernacular façade along the Vine Street Expressway, with winding pathways transecting gardens by Piet Oudolf on the western part of the site, leading to the entrance.

Approaching the entrance, the building is low and subdued, with sunken gardens flanking the lobby and admitting daylight to the tall gallery below. The landscape maintains a loose geometry, partially composed of formal elements familiar from Calder’s work (the circular sunken garden, a steeply pitched triangular awning, a recessed irregular polygon). The site performs at this level more like a diminutive picturesque garden, with Calder sculptures playing the role of follies, and adding an element of surprise and discovery.

Inside, a veranda provides intimate engagement with large-scale mobiles as the space expands vertically, presenting views of the Tall, Small and Open Plan galleries below. A number of large-scale “stabile” sculptures lumber, seemingly stilled mid-step, towards the narrow slit that provides access to the circular sunken garden. Airy mobiles twist and churn impelled by ambient atmospherics and the movement of passersby, whose momentum stirs the sculptures to life. Lighting not only reveals the forms in process (for they are never really complete), but also projects shadows onto walls and floors, extending the play of form, movement and space into a pantomime performed in negative.

“Play of form” is (to quote Calder) á propos, for despite the serious implications of Calder’s work, the dialogues that it instigates between form, space and time evoke a fourth category – that of the poetic. The word “poetic” derives from the Greek “poietikos,” meaning to create or produce, to make. The act of creation is one that transcends space, time and form, it is an act rooted in discovery. The poetics of Calder’s work are prodigious; from the original act of invention that forged them, to the ways in which their inspired permutations propagate forms and spaces across time, to the sheer joy and wonder that they invoke.

Calder’s first works were circus automata made of wire. Videos of Calder performing his circus for children show a round-faced man with curly, disheveled hair, enthralled by the joy of creation, a joy echoed in the children’s laughter. These small circus performances reveal the artist as magician, a poetics of invention, but also of chance, as calculated movements occasionally falter, much to the glee of both artist and observers. Chance, the indeterminate and itinerate forms of arbitrary gestures enacted almost accidentally, in the moment, and perhaps never to be repeated again. Such is the vocabulary of Calder’s work.

This kind of poetics is uncomfortable in most fine art museums, where a staid and stoic seriousness often prevails, perhaps a residual effect of the original “socializing” function once served by museums. Calder’s work seems more at home in a playground, yet the type of play that it induces is not necessarily the frivolous kind, but rather the “serious” play that ignites curiosity, that opens new spatial, formal and temporal – environmental experiences. In this way, the unconventional layout of Calder Gardens is a reflection of the type of spatial resonance described by Focillon, a reverberation of the affects of form evolving in time, of experience as a relationship between nuclei.